From Augustine’s defense of persecution to Locke’s case for religious toleration, from Hobbes’s all-powerful sovereign to Madison’s vision of a diverse republic, this seminar traces how societies have wrestled with the problem of difference. What does it mean to “tolerate” ideas, beliefs, or ways of life we find wrong—or even dangerous?

Together we’ll examine how thinkers across centuries have drawn (and redrawn) the line between error and freedom, heresy and conscience, inclusion and exclusion. Readings include Augustine, Machiavelli, Erasmus, Hobbes, Locke, Jefferson, Franklin, Paine, Smith, Marx, Wollstonecraft, Emerson, Thoreau, Forster, and modern theorists like Michael Walzer and Preston King.

Assignments include a reading journal, short reflections, an analytical essay, and a research project. Depending on enrollment, each student may be expected either to lead class discussion for 30 minutes at some point during the semester or to offer a series of three-minute “leads” to stimulate our discussion throughout the semester.

The goal: to practice civil disagreement and understand why tolerance—far from indifference—is the hard discipline of letting others be wrong.

THE MOST UP TO DATE TIMELINE

Monday, January 19: NO CLASS: Martin Luther King Day

Wednesday, January 21: Introduction (HOMEWORK TO DO TODAY SO YOU DON’T HAVE TO WORRY ABOUT IT WHEN IT’S TIME TO WRITE PAPERS FOR THIS CLASS: download my MLA template linked here in Microsoft Word installed locally to your computer, which you can get by logging into your UNM Outlook webmail page and following these instructions. Find the matrix of nine dots in the upper left corner of your webmail screen (technically known as the “waffle iron”), which pulls up a list of a bunch of the webapps that UNM licenses from Microsoft. Those aren’t the versions of the apps you need, but that waffle iron is the key to installing the actual software to your computer. At the top of that popup menu (to the right of the waffle iron and well above the list of apps) there’s a link with an arrow that says “Office” which takes you to office.com logged in as a UNM user. At the right top of that page is a big button that says “Install Office.” Click that button and follow the instructions, and you should be able to install a copy to your computer.)

Monday, January 26: E.M. Forster, “Tolerance” and “What I Believe” (essays in coursepack, or email me to request a PDF)

Wednesday, January 28: Michael Walzer, On Toleration (Walzer was one of the signers of a famous open letter in Harper’s on justice and open debate a few years ago) (NOTE: please email me for a PDF of the book to read while you wait for the copy you’ve ordered and definitely paid for to arrive, since the UNM Bookstore apparently didn’t order our books)

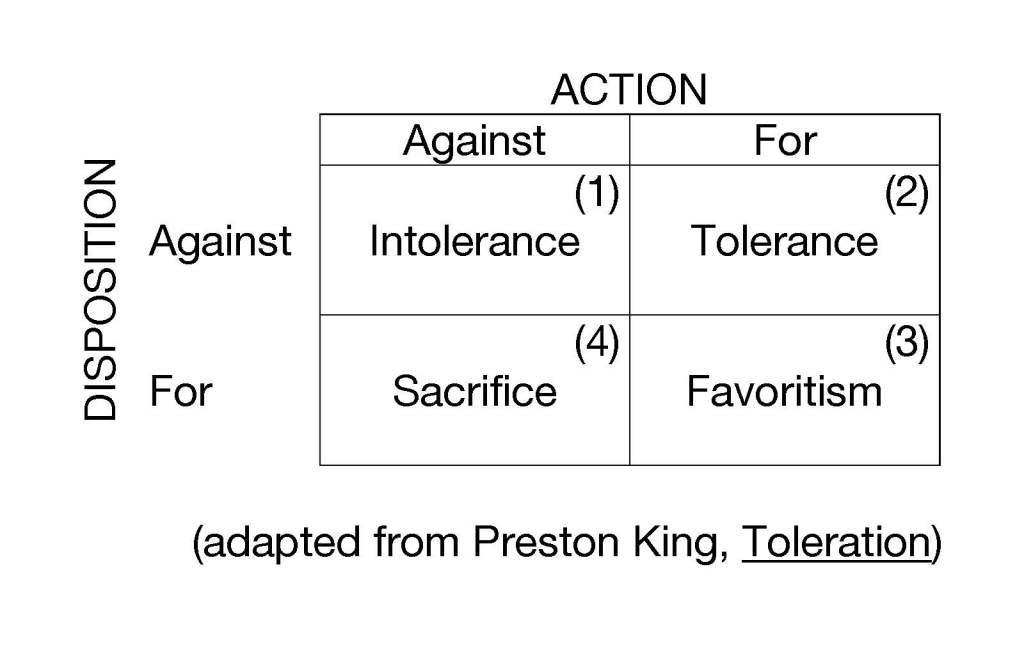

Monday, February 2: John Christian Laursen, “Orientation”; Preston King, Toleration (both prefaces) (both selections in coursepack) (please come prepared with a test case or two we can try out with Preston King’s matrices)

Wednesday, February 4: Geoffrey Chaucer, “The Prioress’s Tale” (in translation in coursepack)

Monday, February 9: Augustine of Hippo, Letter 93 (in coursepack), focusing on Chapters 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.4, 2.5, 2.6, 2.7, and 2.8 (i.e., p. 395-middle of 402); 3.10 (i.e., p. 403); 5.16, 5.17, 5.18, 5.19, and 6.20 (i.e., p. 409-413) AND Dr. Obenauf’s Guide to Writing and Reasoning Like a Scholar (in coursepack)

Wednesday, February 11: John of Salisbury, Policraticus (selections in coursepack from Books 1, 4, and 7), focusing especially on 4.8, 7.2, 7.7, and 7.25

Monday, February 16: Policraticus (continued); The Shorter Analytical Paper is due today! You should come to class with a solid draft, although you will not turn it in. We will spend the day going over my Revision Triage Checklist, which you will use to revise your paper and turn it in on Monday, February 23.

Wednesday, February 18: Policraticus (continued) AND Cary Nederman, “Toleration, Skepticism, and the ‘Clash of Ideas’” (essay in coursepack)

Monday, February 23: Machiavelli, The Prince (LEADS: SAR for ch. 1–3; IA for ch. 4-7; RDB for ch. 8–11; MB for ch. 12–14; JC for ch. 15–18; JE for ch. 19; RG for ch. 20–23; and NH for ch. 24–26); The REVISED version of your Shorter Analytical Paper is due in hard copy at the start of class today.

Wednesday, February 25: Machiavelli, The Prince (continued)

Monday, March 2: Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince (LEADS: IO for the first 1/3 of Chapter 1; HR for the second 1/3 of Chapter 1; JS for the third 1/3 of Chapter 1; RS for Chapter 2; CS for Chapters 3–5; SAR for Chapter 6; and IA for Chapters 7–11)

Wednesday, March 4: Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince (continued)

Monday, March 9: Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan: Chapters 1-18, 21, and 29 (LEADS: RDB for Chapters 1–3; JC for Chapters 4–6; JE for Chapters 7–9; RG on Chapters 10–12; NH for Chapters 13–14; IO for Chapters 15–16; HR for Chapters 17–18; JS for Chapter 21; and RS for Chapter 29)

Wednesday, March 11: Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (continued); at least TWO three of your five six response papers are now due AFTER before Spring Break

Monday, March 16: NO CLASS: Spring Break

Wednesday, March 18: NO CLASS: Spring Break

Monday, March 23: Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (final discussion); John Locke, Second Treatise of Government; AT LEAST TWO THREE OF YOUR FIVE SIX RESPONSE PAPERS ARE NOW DUE AFTER BEFORE SPRING BREAK (i.e., today!)

Wednesday, March 25: John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration

Monday, March 30: Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations: Book 1: skim as much of Book 1 as you can, at least through 1.8, but you should actually read pp. 1-26 because it’s the most important; Book 2: please read Chapter 2.2 (pp. 488-503) for Smith’s historical analysis of ancient Rome and some of his comments against slavery; Book 4: you can skim Chapter 4.2 (pp. 568-593), a topical chapter on tariffs and trade wars where Smith famously mentions the “invisible hand”; Book 5: you can skim much of Chapter 5.1 (pp. 879-1031), but please read with closer attention Part II (pp. 901-916) and the articles on education and the conclusion (pp. 962-1031), where Smith’s good nature and wit shine through as he makes some of his most relevant comments for our class’s focus. Please come with at least three questions and at least two connections to our other course readings.

Wednesday, April 1: Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (continued); Proposal for term paper is NOW due today (aim for about a one-page abstract followed by a few pages of annotated bibliography)

Monday, April 6: Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto

Wednesday, April 8: Franklin, “Toleration in Old and New England”; “The Boston Pamphlet” (both in coursepack)

Monday, April 13: Thomas Paine, Common Sense (in coursepack)

Wednesday, April 15: The Declaration of Independence (in coursepack)

Monday, April 20: Alexander Hamilton, Federalist #1; James Madison, Federalist #10 (both in coursepack) (try to get in at least one of your remaining response papers by the end of this week)

Wednesday, April 22: The U.S. Constitution (in coursepack)

Monday, April 27: Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Wednesday, April 29: Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (continued)

Monday, May 4: Emerson, “History,” “Self-Reliance,” and “Friendship”; Thoreau, “Civil Disobedience,” “Slavery in Massachusetts,” and “Life without Principle”

Wednesday, May 6: Course summary and final remarks; your term paper is due by email as a Word document by the start of class unless we have agreed upon an extension! The rest of your response papers are also due by today!

IMPORTANT COURSE DOCUMENTS

- What Good is Tolerance? Syllabus, Spring 2026. This is the same document I circulated by email and discussed the first day of class. Most of the information is reproduced below on this website. The timeline, above, will always be up-to-date.

- Sample MLA Document (template) for you to download and use as the basis for all your written work in this class. I last updated this on 1/20/26 and consider it a work in progress. If you use this document, your margins, typeface, line spacing, etc. are likely to be correct. It is crucial that you follow the conventions of style and formatting, and this document will put you in a strong position to make sure your paper is 12pt Times New Roman, double spaced, 24 lines per page, with margins that print at 1″. You should not change the settings unless you know what you are doing and have good reason to do so. You can get a copy of Microsoft Word through your UNM Webmail (Google Documents, Apple Pages, etc. will not produce a proper MLA-formatted document).

- Dr. Obenauf’s Guide to Writing and Reasoning Like a Scholar. I consider this essential to your success in this course. This is the same version as in your coursepack. I will likely refer you to specific sections of it in my comments on your papers. Read it carefully and ask if you have any questions about the advice in it.

- My Revision Triage Checklist, last updated in February 2026.

LINKS AND RECOMMENDED READING

(I WILL UPDATE THIS LIST FREQUENTLY THROUGHOUT THE SEMESTER)

- The Oxford English Dictionary off-campus proxy server login through UNM Libraries (on campus: http://www.oed.com)

- The Shadow Syllabus by Sonya Huber, which I wish I’d written for my students. It’s an imaginary syllabus of good advice that you can use to get the most out of this class, and probably most of your classes, to supplement the actual binding syllabus to go with any course.

- “Why We Must Still Defend Free Speech” by David Cole, national legal director, ACLU, in the New York Review of Books, August 28, 2017 issue. Given how far the country has swung towards intolerance since 2017, even on the left, it’s worth mentioning that this fine essay explains the difference between speech and action and uses our keyword “tolerance” in a nuanced way that may help you to understand some key concepts of our seminar and the ways they play out in current debates.

- George Lakoff, Metaphor, Morality, and Politics. You can print the PDF of the article from this site. The cognitive linguist Lakoff has really influenced me. This article contains an early and very distilled version of his main argument, which has been that liberals and conservatives fundamentally see the world differently. Even though we may think our political opponents are crazy, he explains that they are not; they just have a different sense of morality, which is tied up with the metaphors we use to understand a complex world. If you’re interested, I also recommend Metaphors We Live By and Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think. There are a few other good ones, but that should be enough to get you started.

- No, There Isn’t a Constitutional Right To Not Wear Masks: To Argue Otherwise Misconstrues the Constitution and the Values Undergirding it by Helena Rosenblatt, professor of history at the Graduate Center CUNY and author of The Lost History of Liberalism: From Ancient Rome to the Twenty-First History. This “Made by History” essay in the Washington Post, 20 August 2020, has at its heart a discussion of ideas forwarded by John Locke and Adam Smith — ideas by these very thinkers that we will be exploring in our class later this semester.

- “Our Culture of Contempt: The problem in America today is not incivility or intolerance. It’s something far worse” by Arthur C. Brooks in the New York Times, in connection with Hobbes’s paragraph on contempt in the Leviathan (p. 120).

- “Our Consensus Reality Has Shattered” by J.M. Berger in The Atlantic, 9 October 2020, calls to mind the same sorts of issues Hobbes raises about how we can know what is true.

- “Trump Destroyed the Most Important Virtue in America“ by Tom Nichols in The Atlantic, 20 January 2021. The American Founding Fathers, Nichols writes, “knew that seriousness is the greatest requisite for a stable democracy, because it allows us to think beyond the moment and to accept the weight of duty and communal responsibility. The many other civic virtues—prudence, engagement, respect, tolerance—proceed from seriousness.”

- “Coexistence is the Only Option” by the great Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic, also on 20 January 2021. She argues that seditionists need a pathway back into the fold of American society, for there are millions of Americans who sympathize with the Capitol insurrection who we have to live with (or in other words tolerate).

- “Why 1850 Doesn’t Feel So Far Away” by Joanne Freeman, a Yale historian, in the New York Times on January 29, 2021. She writes that democracy doesn’t require absolute unity, but rather that “in a sense, conflict is its core. A truly democratic government enables people of all kinds to express their views and serve their interests through protest and the democratic process, itself grounded on debate and compromise, arguments, electoral and legislative contests, and competition — though not the rule of force.” She adds that for that reason, “democratic governance requires clear lines in the sand beyond which dissension cannot go. The Trump supporters who mobbed the Capitol seeking to assault lawmakers and overturn an election crossed that line. They physically attacked American democracy — its processes, its officeholders, its structural home.”

- “Most Republicans See Democrats Not as Political Opponents But as Enemies” by the Washington Post‘s Philip Bump, February 10, 2021, which uses a “thermometer” to gauge Americans’ degrees of dislike, tolerance, and endorsement for each other.

- “The Founders Were Wrong About Democracy” by the conservative writer for The Atlantic David Frum, 15 February 2021, a long essay that touches on many of our class themes and that explores ideas from Federalist No. 10 in particular. I realize that we won’t be reading that until much later in the semester, but it could be worth checking out as we begin to discuss the roots of democracy and their connection to tolerance.

- “The Republican Party Is Now in Its End Stages: The GOP Has Become the Communist Party of the Soviet Union of the Late 1970s” by Tom Nichols for The Atlantic, 25 February 2021. I’m not sure why I’m posting so many pieces from that magazine by moderate conservatives and ex-conservatives, but here we are. I think you’re going to like this one.

- “America Without God” by Brookings Institution senior fellow Shadi Hamid for The Atlantic April 2021 issue, a fine essay that considers many of our course themes, ranging from the civil religion of American democracy to problems of tolerance and love. It’s about the decline of religiosity and its implications for civic life, and so much more. I think you’re going to like this one.

HOW TO GET THE MOST OUT OF THIS COURSE

What you get out of this class depends on what you put into it.

“What Good is Tolerance?” is centered on primary sources. In most cases, I will be interested in how you respond to the ideas and themes in our readings without regard for what anyone else has said about them. I am looking for your most honest responses and interpretations based on the evidence you gather from our sources. Without fear of saying the “wrong” thing, or pressure to say the “right” thing, you will gain confidence in summarizing texts in your own words and generating your own ideas about them based on evidence you cite.

To help you slow down and practice reading, thinking, and writing carefully, most weeks you will need to spend between five and ten hours outside of class preparing for our seminar sessions. This course assumes that much of that time will be spent reading and writing without digital distraction—ideally with print texts, paper notes, and handwritten revision. We won’t use Canvas in this class—you’ll use Microsoft Word to produce MLA-style documents, which you’ll print out and turn in as hard copies. I’ll read your papers with a pencil in my hand and return them with notes you will then review and use as you work on your next paper. When we’re in class together, we will rarely use the projector for videos or PowerPoint; rather, we’ll give each other our full attention by putting away our electronics and listening to what each person is really trying to convey through their words.

Rather than relying on summaries and other people’s interpretations—which may be inaccurate or may cloud your analysis of the course readings—you should read slowly and with a dictionary, taking notes and coming to class with questions you were unable to answer on your own. If you don’t already own a decent dictionary, you should consider buying one. A print dictionary will allow you to look up unfamiliar words without getting sucked into your phone. It is normal to be a little confused at times. That is part of the process. There are no shortcuts.

You are expected to be the sole creator of all work you submit and of every idea you raise during class discussion. This includes resisting the temptation to use AI tools like ChatGPT, Grammarly, or similar software. They can imitate certain skills, but they cannot give you the experience of doing the work yourself—and they can lead you astray. This course is designed to give you the rare opportunity to build your own voice, with your own reasoning, from the ground up. If you are ever in doubt about whether it is acceptable to use a particular resource for this class, you should ask your instructor. Before you submit each assignment, ask yourself this question: Did I do this work myself, yes or no?

I look forward to seeing what you’ll discover for yourself this semester.

YOUR GRADE

The grade you earn on each assignment in this course is less important than the feedback you receive and the progress you make over the course of the semester. Grades are a necessary evil: grades give you an idea of how you are doing, but you should not fixate on them. Do your best and strive to do even better next time.

30% Participation, including class discussion leads

70% Written work:

20% Response papers

20% Shorter analytical paper

30% Term paper

Your semester grade will follow the Honors College’s unique grading system according to these criteria:

A semester grade of A+, A, or A– will be recorded on your university transcript as an A. An “A” signifies exemplary work that meets Honors expectations and will compute into your academic GPA.

A semester grade of B+ through C+ will be recorded on your university transcript as “CR.” A grade of Credit in this course signals that you participated meaningfully in class discussion and that you made an earnest attempt to meet the basic norms of scholarly writing even if your work did not consistently meet Honors-level expectations for writing and rigor. You will receive credit towards graduation for your satisfactory work in this class, but your grade will not factor into your academic GPA.

A semester grade of C or below will be recorded on your university transcript as “NC.” A grade of No Credit signals a failure to meet basic conventions of scholarly work, such as respect for deadlines, formatting, grammar, accuracy in citations and bibliographies, and/or significant problems in attendance and participation. Even if your points add up to a passing grade, it is not possible to pass this course if your final project is incoherent or lacks appropriate citations or an accurate bibliography. Thus, a grade of NC indicates unacceptable work and is not computed into your GPA or counted towards graduation.

I believe that every student enrolled in this seminar is capable of earning an A for the semester. Because I do not grade on a curve, nothing would delight me more than to turn in all As in May.

CLASS PARTICIPATION

Attendance: We all benefit from hearing your perspectives in class discussion. I will lower your participation grade for each unexcused absence. After four unexcused absences, therefore, you will no longer be able to earn a passing grade in the class. Your consistent attendance and contribution to class discussion are crucial to the success of this small seminar. And although I expect you to be ready to begin on time, it’s better to be late than not to come at all. Consistent tardiness will affect your participation grade in proportion to the consistency of your disruption. Please keep in touch with me if you must miss class. If you are experiencing physical or academic barriers, or concerns related to mental health, physical health and/or COVID-19, please consult with me after class, via email, or during office hours. I want to help you succeed in this class, and I will do everything within my power to shepherd you through to May. We will work together on a case-by-case basis as issues arise.

Book policy: Bring the book we’re reading to every class session. We will need to cite evidence for every claim we make. To practice quoting the text extensively during class discussion in preparation for your papers, we will all (literally) need to be on the same page. I have prepared a photocopied coursepack of shorter readings and ordered the most inexpensive editions I could find of longer books to make sure that you can afford the materials for this class, and you are expected to use these physical printed materials, in the exact editions I have requested. Our classroom is both a NO-B.S. ZONE and a safe space to try out new ideas; the best ideas are anchored in concrete evidence; without your book, you cannot cite evidence for your claims, and therefore you cannot participate meaningfully in discussion. Since you may be dismissed from class and marked “absent” for the day if you do not have your book with you, if you realize you’ve forgotten your book, you should tell your instructor immediately and ask permission to share with a classmate or to use an electronic version for that day only.

Electronics use: The emphasis in a seminar is on conversation. Please put away your electronic devices when you are in class so that you can devote your full attention to what your classmates are saying and to what you can contribute. I ask that you use PRINT editions of the texts we will be discussing so that you can leave your phones, computers, tablets, e-readers, and other distractions in your bags. I don’t want for you to forfeit your participation points for that day. Pen and paper will do fine for your note-taking in Honors.

Participation and preparation: Honors seminars are neither lectures nor bull sessions; active attendance is a part of participation, and so your presence alone does not guarantee participation points. You are encouraged to contribute when you have something thoughtful to say…which means coming to class thoroughly prepared to discuss the day’s readings with an open mind. The best way to prepare is to read the course materials attentively, looking up unfamiliar words and concepts, and generally considering the major issues of the works before we begin our discussions.

Leading class discussion: Depending on course enrollment, you will be expected to lead class discussion in one of two ways (or possibly both). If enrollment drops to approximately one dozen students in the course, you will be charged with leading class discussion for at least 30 minutes (and likely the entire class session after my opening remarks) at some point during the semester. You should email me several days ahead of time with your tentative questions and plan of attack so that I can offer additional questions and offer some hints for the text you will be teaching.

Leads: In order to minimize duplication, if enrollment is near capacity, you will instead be assigned to prepare a series of BRIEF (two- to three-minute) “leads” on a rotating basis to stimulate our discussion throughout the semester. I will post these on the website and announce them in class ahead of time. You should begin with a CONCISE (no more than one minute, and ideally just two or three sentences) original summary of your assigned section to jog your classmate’s memory of the section. I am specifically requesting that you not bog down class time with lengthy summaries. We have all done the reading. We do not need a page-by-page account of what we have already read. Being able to write a brief summary without relying on ChatGPT, Wikipedia, or any other source is an important skill for you to develop. This will be good practice for you, and it will help the class stay focused on your section. Then, help the class draw a link between the themes of your section and the themes of the course—ideally, by finding a test of tolerance that we could put on Walzer’s or Laursen’s scales or King’s matrix, or by connecting it in some other way to our questions of tolerance and intolerance within specific historical contexts. While you might mention other relevant material from elsewhere in the text, you should try to limit your comments to your passage so as to avoid overlapping with other students who are taking the lead on other parts of the book. You must have some sort of argument for your lead: you can’t just say that you found something “interesting”—though you could certainly use that as a springboard. You must explain why it seems surprising at first, and what your observation suggests about our course themes. You are obviously free to agree or disagree with our texts.

Reading journal: In addition to your normal class notes, you will need a separate notebook—a reading journal—to use for reflection throughout the semester. For each reading, I will announce some reflection questions for you to consider in your private reading journal. I recommend tackling the questions before attacking the reading so that you can see how your ideas compare with those of the text. This will take approximately one to two hours per text and it is a significant part of this course. You will draw on your personal responses in your short response papers, and your observations about the readings will help you prepare for class discussion. This reading journal is strictly confidential—you will never, ever be required to share its contents with me or with any of your classmates. You are expected to keep up with it.

Following up by email: Although Honors expects all students to contribute to our daily seminar discussion, you may not be able to express every idea that you would like to explore in our limited time. I encourage you to email me with your observations, questions, or even links to relevant articles. Past students have found it helpful to articulate an idea by explaining it in an email to me, and this is one way introverted students in particular can show that they are truly engaged in the course.

WRITTEN WORK

Although consistent and thoughtful class participation is crucial to your education (and hence your grade), the slow, careful work of a scholar is largely a solitary activity. And, in contrast to in-class participation, written work is much more objectively assessed and improved over time. For these reasons, your written work accounts for the bulk of your grade in this course. I will provide ample feedback on your papers, including marginal annotations and typed comments so that you can continue to improve your writing, no matter how well you write at the start of the term. You should review my notes carefully.

I can only help you identify your strengths and weaknesses if the work you submit reflects your actual abilities. You will not be permitted to rewrite any of your papers in this class. It is important that you do your best the first time so that I can respond with advice that will help you take your writing and thinking to the next level.

I will spend significant time responding to your work, and so I have some specific requests about how you format your documents so that I can streamline my grading. I would much rather spend my time commenting on your ideas and argumentation than on your formatting and grammar. You don’t need me to tell you things you already know—if you rush through your drafts and skip the revision process, my feedback will be less helpful to you than if I am able to respond to your strongest effort. Since you will not be permitted to rewrite any of your papers in this class, I urge you to do a good job the first time and request guidance and extensions if necessary.

I take it as a given that you will use the MLA template I have provided on the course website so that you can focus your energy on your writing and argumentation and I can focus my energy on responding to your writing and argumentation. I have also provided a Guide to Writing and Reasoning Like a Scholar in the coursepack for this class to help you produce the sort of writing we are looking for in Honors, regardless of what writing classes you may (or may not) have had in high school or college.

For this class you will need to install Microsoft Word to your computer (and NOT just use the online version, or Google Docs, or Pages, etc.). You can get it for free as a UNM student through your webmail page. Look for the matrix of nine dots in the upper left corner (technically known as the “waffle iron”), and click it to reveal a list of various webapps. You don’t want those webapps, but above that list is a link with an arrow that says “Office.” Click that and you’ll go to office.com but logged in with your UNM credentials. At the top right of that page there’s a big button that says “Install Office.” Click the button and follow the instructions. Once you have Word on your computer, you’ll be ready to download my MLA template from the course website that will enable you to produce properly formatted MLA documents.

Since you will not be permitted to rewrite any of your papers in this class, I urge you to do a good job the first time and request guidance and extensions if necessary. That said, you have the tools to get full credit for all of your work. I would much rather spend my time commenting on your ideas and argumentation than on your formatting and grammar. You don’t need me to tell you things you already know—if you rush through your drafts and skip the revision process, my feedback will be less helpful to you than if I am able to respond to your strongest effort. To help nudge you towards using the course materials sooner rather than later, this semester there will be a penalty of one letter grade for each significant formatting or proofreading issue. I look forward to seeing what you come up with!

To reiterate, I have provided you with a thorough guide to writing and reasoning like a scholar in your coursepack, which will help you teach yourself how to meet the expectations of the formal analytical writing in this class, including the analytical portions of your term paper. You must proofread your work carefully before you turn it in. There will be numerous other handouts and tools provided to you this semester to help you succeed in this class. You should use these tools to hold yourself accountable and to help yourself develop writing and critical thinking skills that will serve you for the rest of your life. Please ask for help if you are struggling to meet these expectations.

You are expected to follow the latest MLA style guide and to document your sources meticulously. This is Honors! For example, all work should be exactly double-spaced in a 12-pt. Times New Roman typeface, rendered with 1” margins, and therefore 24 lines of text per page; the page number and your name must appear in the upper right corner of each and every page. Please print all documents single sided. You must neatly staple or paperclip your pages together: loose or crimped pages will not be accepted. I will not grade any paper that fails to meet the minimum expectations for length, formatting, proofreading, or rigor of citations and bibliographies. A template is available on this website. For additional examples, consult your MLA Handbook and see http://style.mla.org.

As you write, you should consult references like The Elements of Style, a good dictionary, your MLA Handbook, and Dr. Obenauf’s Guide to Writing and Reasoning Like a Scholar. I expect your very best. As a rule of thumb,

- A papers open with an introduction that gives sufficient context without overwhelming the reader with irrelevant information and offer a concrete thesis statement at the end of the introduction. The body of an A paper is meticulously organized and well polished, taking a serious tone as it persuasively guides the reader through rigorously cited evidence and careful original analysis. Its conclusion takes the analysis a step further and considers the broader implications of the project’s analysis, avoiding recapping or simply summarizing what has already been said. The bibliography is accurate. In short, an A paper follows the conventions of style and formatting described in the MLA Handbook and in Dr. Obenauf’s Guide to Writing and Reasoning Like a Scholar.

- B papers make an earnest attempt at all of the traits of an A paper, but do not fully meet these expectations.

- C papers struggle to meet these basic expectations but show a sincere attempt at intellectual honesty and rigor.

- D papers make reasonable use of evidence but are too incoherent to build a persuasive argument.

- F papers are intellectually dishonest or otherwise fail to meet the most basic expectations of college writing as described in Dr. Obenauf’s Guide to Writing and Reasoning Like a Scholar. Coherent papers may be returned with an F if they do not conform to the norms of formatting, if they do not present sufficient evidence to build a persuasive argument, or if they do not respond to the paper prompt as assigned. Papers below the minimum length requirement cannot answer the assignment as described and so they will be returned with an F.

All work must be submitted in hard copy at the beginning of class on the day it is due. I am reasonable about extensions, but you must talk to me—or e-mail me—ahead of time if you think you will need an exception. Otherwise, late work will be penalized one letter grade for each day it is late.

There are three kinds of papers you will submit in “What Good is Tolerance?”:

- Your six short response papers should be no less than one full page but no more than two full pages of text, double spaced, plus an accurate Work (or Works) Cited page. You may submit them at any time, but you must submit at least three of them before Spring Break. These short reflection essays are likely to expand on topics you first explored in your private reading journal, but there is no assigned topic: they merely need to relate to the class themes or readings. NOTE: ON 3/2/26 we agreed to reduce this to five response papers, with the first two now due after Spring Break.

While these essays are likely to be personal and reflective in nature, you must argue them with concrete evidence. Part of the challenge is to strike a balance of personal and analytical commentary, writing neither an entirely personal essay nor an entirely analytical paper. A personal anecdote drawn from your life would make a suitable opening; you might then comment on how one or more of our recent readings deals with a similar issue, using rigorously-cited quotations from course readings or other materials you encounter; to conclude, return to your opening comments. In discussing course materials, you should not consult any outside sources, summaries, or commentaries, or using AI tools like ChatGPT.

In order to avoid the pitfalls of arguing too broadly (such as by attempting to make sweeping suggestions about “society” or “human nature”), you should argue with concrete examples, which can include personal anecdotes and quotes from your journal. Anecdotes from your own experience can make a useful point of comparison for understanding how other people in other times and places dealt with similar situations.

You are encouraged to write on political themes, and you should not worry about my political sensibilities. I am interested in hearing your stance and giving you the opportunity to articulate your understanding of philosophy in light of current events. In order to avoid the pitfalls of arguing too broadly (such as by attempting to make sweeping suggestions about “society” or “human nature”), you might focus your commentary by briefly citing a relevant article from a newspaper of record (such as The Albuquerque Journal, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, or The Washington Post).

I will comment on these lightly. Since they will be graded on a pass/fail basis, as a general rule they will not be accepted late. A pattern of especially good or especially sloppy work will affect your grade.

- Shorter analytical paper (5-7 pages): With Dr. Obenauf’s approval, you are to choose a work of literature of historical significance composed before 1975 such as a play or a novel. Most plays by Shakespeare would work well for this assignment; I encourage you to use Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Then, copy over the first paragraph I have provided below, inserting the relevant information for the text you will be analyzing. Subsequent paragraphs will describe the key events you list in the introduction and analyze them according to Walzer’s and Laursen’s scales. Your conclusion must take your analysis a step further, explaining the significance of your findings in their historical context.

The political philosopher Michael Walzer has proposed five kinds of toleration: resignation to difference for the sake of peace; a benignly relaxed, passive indifference to difference; a principled recognition that others have rights even if they exercise them in unattractive ways; openness or even curiosity; and finally, an enthusiastic endorsement of difference (On Toleration 10-11). In critiquing Walzer’s scale, the political historian John Christian Laursen has clarified that “respect, endorsement, and celebration” are as far from toleration as is “organized, systematic, violent persecution” (“Orientation” 3). Laursen instead proposes a simpler scale, with “organized, systematic, violent persecution” at one end and “respect, endorsement, and celebration” at the other (3). One work that deals with tolerance and intolerance is [title of the work you will be discussing], by [author’s full name] (year). In this work, [brief 2-3 sentence or so summary of the work]. In [the work you will be discussing], [author’s last name] points to [three, four, or five] main events that illustrate tests of tolerance. First… Second… Third… [etc.] Taken together, these events suggest that [your interpretation of tolerance or intolerance in the work].

You may not analyze a work we have discussed in class. For this assignment, you must use the paragraph I have provided above as the basis for your introduction. Your paper must have a clear, sophisticated thesis at the end of the first paragraph. Your essay must demonstrate your thesis through rigorous textual evidence and clear argumentation. You may not modify, alter, or expand on the scales of tolerance outlined by Walzer or Laursen; you may comment on the limitations of those scales only after showing how your analysis draws on their frameworks. If you wish to use Preston King’s matrix, you may do so only as part of your conclusion.

You are not expected to bring in any outside research as part of this analysis, though you can quote additional material from Walzer and Laursen as necessary. Any additional research must be highly relevant to your argument. It is more important that you use Walzer’s and Laursen’s scales in conjunction with your primary source to provide new historical insights into the social climate within which your author was writing. Finally, you will need to produce a Works Cited page following MLA conventions.

- Term paper (10-15 pages): This paper should take the approach described in my Guide to Writing to begin with a question and avoid making strong assertions which can be refuted easily. Working with Dr. Obenauf, you are to develop a topic of your own choosing that centers on issues of tolerance and intolerance, either in the past or the present. For example, you may wish to explore tolerance in literary works, in other countries at past or present, or in contemporary American society and politics. You could explore legal cases, sociological issues, or pretty much anything that provides clear examples of tolerance and intolerance that you can analyze according to Walzer’s and Laursen’s scales of tolerance (and King’s matrix, if you’d like).

By the tenth week of the semester, you must submit a one-page proposal describing the main question you hope to answer through your project and a tentative hypothesis; this document must also include an annotated bibliography of at least five works that you think will be helpful to you.

Your paper must demonstrate a deep understanding of the theoretical materials from this course; you are expected to use the scales of tolerance to guide your interpretations, and you must explain them, in your own words, in such a way that an uninitiated reader can understand what they are and how you are using them. You may also find it useful to refer to some of the other readings from the course, explaining relevant passages and building on them in a way that someone unfamiliar with the materials can understand. Your paper should have a clear thesis statement, but you should not formulate it until you have drafted your paper and discovered it through the writing and revision process.

A NOTE ON CITING SOURCES ACCURATELY

Through these assignments, you will get lots of practice citing your sources. Your Works Cited page is perhaps the most important element of college writing because it shows your reader how to check the citations in your paper. You should plan ahead to create the bibliographic entries based on the sources you cite, and then painstakingly double- and triple-check them for accuracy. For reasons I explain in greater detail in my Guide to Writing and Reasoning Like a Scholar in your coursepack, it is very important that your Works Cited pages be accurate.

Bibliographies allow your reader to confirm that what you have said is true; inaccurate entries cast doubt on the entirety of your argument, and so they are anything but busy-work. You must devote as much attention to detail at the end of your project as at the beginning. A meticulous bibliography is part of a gestalt of rigor and intellectual honesty expected in Honors that signals your devotion to truthfulness and openness in your work.

I have a zero-tolerance policy for inaccurate citations. You are expected to quote your sources faithfully and to cite them rigorously. Anything less is a form of academic dishonesty and could lead to dismissal from the class. Working directly with primary sources is at the core of what this class is all about. You are expected to choose appropriate evidence to drive each point you make, and you are equally expected to produce your own in-text citations and your own works cited entries based on the materials you have used. Your sources should, as a rule, be the versions I have assigned for this course.

Inaccurate quotations or citations will be assumed to be produced by a citation generator or by AI and, as evidence of academic dishonesty, will force me to report your paper to the Dean of Students and to recommend that you be dropped from the class. Your learning in this class depends on you producing the work with your name on it and not relying on anyone else to do it for you. This is your only warning: if you submit work with citations that do not match the actual sources you used in your paper, I will be forced to initiate an academic dishonesty case against you. I implore you—do not outsource this most fundamental part of college writing!

Any student who lists an edition other than the exact version cited in the paper at hand will not receive credit for the assignment, whether it is a short response paper, a shorter analytical paper, or a final project. You will not be permitted to revise or resubmit your essay, and so a brazenly misleading bibliography can prevent you from earning an A for the semester, and it may well prevent you from passing the course.

Fortunately, accurate bibliographies are not difficult to produce. You should resist the temptation to use an online citation generator, ChatGPT, or any other shortcut. It is not worth the risk! Instead, you should refer to your MLA Handbook and other reputable guides and produce the entries yourself. If you have any doubts, you should ask your professor for guidance.

That said, honest mistakes are part of the learning process. The zero-tolerance policy applies to citations that clearly do not correspond with the relevant information they purport to document. I know it can feel safer to rely on a generator when you’re worried about getting every comma in the right place. But part of the value in doing it yourself is that your first attempts will have their own quirks—and that’s an inevitable part of the learning process. The MLA Handbook is a required text for this class because it shows you how to make your own citations based on the materials in front of you. (Tip: what MLA calls “location” means the location within the sources, such as a range of page numbers within an anthology; “place of publication” refers to the city or country where the work was published and is not generally needed for editions produced in the last hundred years.)

Before you submit each assignment, ask yourself this question: Did I do this work myself, yes or no?

WHAT SORT OF HELP IS OK?

You may seek help with all stages of the writing process, but you must be the sole author of all work you submit in this course. Submitting material as your own work that has been generated on a website, in a publication, by an artificial intelligence algorithm, by another person, or by breaking the rules of an assignment constitutes academic dishonesty. It is a student code of conduct violation that can lead to a disciplinary procedure. It should go without saying that learning the course material depends on completing and submitting your own work.

Off-campus paper writing services, problem-checkers and services, websites, and AIs can produce incorrect or misleading results. Indeed, consulting outside sources is likely to derail your thought process, as is the use of AI tools such as ChatGPT.

Instead, I urge you to enlist your friends and family to help you proofread your papers—and to read your own prose out loud.

You may wish to reach out to our Honors librarian over at Zimmerman Library, Adrienne Warner by email at adriennew@unm.edu or by scheduling an appointment through her faculty page, https://ulls.unm.edu/people/directory/w/warner-adrienne.php

Also, the Center for Teaching & Learning (formerly CAPS), offers resources at https://ctl.unm.edu/ that you may find helpful at all stages of the writing process.

Above all, if you are ever in doubt about whether it is acceptable to use a particular resource for this class, you should ask your instructor.

HOW WE WILL HANDLE PROVOCATIVE AND OFFENSIVE MATERIAL

This semester we will be examining cultural and historical legacies that span hundreds of years—some of them quite wonderful and others utterly horrifying—to better understand our own society and our place within it. For example, we will trace the roots of modern racism, sexism, xenophobia, and other forms of coercion from their ancient and medieval roots as they manifest in forces and ideas such as the Great Chain of Being. I sincerely hope you use this information to build a more just world.

The syllabus for this course is packed with works chosen for their literary, philosophical, political, historical, and aesthetic significance. No historical artifact or document can capture the entire essence of the lived experience of a particular time or place; we will read these works for what they reveal about the broad expectations of their first audiences. But rather than judging the past by our standards, our time is best spent uncovering what old books suggest by thinking as historians, literary scholars, and anthropologists. For example, we will trace the roots of various kinds of bigotry—as well as pushback against injustice—from the classical world through the present. While I hope you find something of personal interest in our reading list, when you disagree with a perspective I encourage you to grapple with the seeming contradictions and internal inconsistencies within works and among various texts as a way to discover the forces that motivated people who held view different from your own. Indeed, we will be reading, discussing, and writing about ideas that will make you uncomfortable.

Considering concepts in their historical contexts should not be construed as endorsement of those memes. Our aim is not to litigate the truth or morality of the texts on our syllabus; our goal is to understand these works on their own terms for what they suggest about how other people lived and what they thought. To that end, as a general rule we will not be censoring our works. We acknowledge that when we analyze primary literary works within their historical contexts, the words and concepts belong to the author rather than to the scholar who is quoting part of a text that is germane to the topic at hand. In your papers, you should reproduce quotations precisely, though you may paraphrase words and passages in your subsequent discussion to avoid using epithets in your own prose. In our seminar sessions, at times your instructor may take the reins and read certain passages out loud so that no student is forced to read them in class, though, again, we recognize that the words and ideas belong to the author and not to the person reciting them.

Per Section 2220 of UNM’s Student Handbook, The Pathfinder, “As an institution that exists for the express purposes of education, research, and public service, the University is dependent upon the unfettered flow of ideas, not only in the classroom and the laboratory, but also in all University activities. As such, protecting freedom of expression is of central importance to the University. The exchange of diverse viewpoints may expose people to ideas some find offensive, even abhorrent. The way that ideas are expressed may cause discomfort to those who disagree with them. The appropriate response to such speech is speech expressing opposing ideas and continued dialogue, not curtailment of speech. The University also recognizes that the exercise of free expression must be balanced with the rights of others to learn, work, and conduct business. Speech activity that unduly interferes with the rights of others or the ability of the University to carry out its mission is not protected by the First Amendment and violates this policy.”

While I would never pressure any student to say something simply because it’s what you think I would want to hear, I encourage you to speak up when you have something relevant to say. Respectful debate and free inquiry are cornerstones of Honors seminars, so long as our discourse is germane to the seminar and the topic at hand. You do not have the right to derail class discussion.

Finally, at times this semester we may be discussing passages that could be disturbing, even traumatizing, to some students. If you ever feel the need to step out during one of these discussions, either for a short time or for the rest of the class session, you may always do so without penalty. You will, however, be responsible for any material you miss and should make arrangements to review notes with one or your classmates or to see me during office hours.

STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES

Once students successfully complete “What Good is Tolerance?” they will be able to:

- Analyze, critically interpret, and evaluate primary works of literature and politics that reflect issues of tolerance and intolerance, such as Machiavelli’s The Prince, Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration, and Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter within their interdisciplinary cultural and historical contexts.

- Construct persuasive arguments and increase writing proficiency through analytical essays characterized by original and insightful theses, supported by logically integrated and sound subordinate ideas, appropriate and pertinent evidence, and good sentence structure, diction, grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

- Compare modes of thought and expression across a range of historical periods and/or structures (such as political, geographic, social, cultural, philosophical, and intellectual); for example, the role of tolerance in American Democracy as opposed to the English Middle Ages.

- Demonstrate knowledge that integrates ideas and methods from different disciplines; for example, how to evaluate literary, philosophical, and historical works as manifestations of changing attitudes towards tolerance and intolerance.

EVEN MORE FINE PRINT

Responsible Learning and Academic Integrity: Each student is expected to maintain the highest standards of honesty and integrity in academic and professional matters. UNM reserves the right to take disciplinary action, up to and including dismissal, against any student who is found guilty of academic dishonesty or otherwise fails to meet the standards. Per UNM policy, any student judged to have engaged in academic dishonesty in course work may receive a reduced or failing grade for the work in question and/or for the course. Academic dishonesty includes, but is not limited to, dishonesty in quizzes, tests, or assignments; claiming credit for work not done or done by others, including the use of AI such as ChatGPT; hindering the academic work of other students; misrepresenting academic or professional qualifications within or without UNM; and nondisclosure or misrepresentation in filling out applications or other records. These rules exist to protect your learning. If you do the work yourself, you’ll discover things you never would have noticed otherwise—connections, questions, and even disagreements with the text that no summary or algorithm could hand you. That’s where the real satisfaction comes from, and it’s why the work in this class is worth doing honestly. Therefore, you are responsible for personally creating each step of every assignment you submit in this class. Taking shortcuts, including consulting summaries of the readings, ChatGPT or other AI models at any stage of the writing or revision process, citation generators, etc. is a form of academic dishonesty which will not be tolerated. Plagiarism is a grave offense that will result in a grade of “F” for the assignment and that could lead to dismissal from the Honors College or expulsion from the university. Any student who submits a paper with any component written by someone else—including by ChatGPT or other generative AI models—will receive a grade of “F” on the assignment and a grade of “NC” for the semester. The emphasis in our class on primary sources means that, with a few clearly defined exceptions, you should consult no resources outside of the books we are discussing in the editions I’ve specified in this syllabus. Inaccurate quotations or citations will be assumed to be produced by a citation generator or by AI and, as evidence of academic dishonesty, will result in my recommendation to the Dean of Students that you be dropped from the class. There will be no second chances. You may lose your scholarship. So, before you submit each assignment, ask yourself this question: Did I do this work myself, in its entirety, yes or no? The point of these policies is not just to stop cheating—it’s to make sure you get the full value of the work you put in. This class is designed to give you the kind of deep engagement with ideas, texts, and writing that can’t be outsourced or shortcut. By doing your own work, you contribute to a community where grades mean something, ideas are genuinely exchanged, and your degree reflects real achievement. For additional information on plagiarism and other university policies, please consult UNM’s Student Handbook, The Pathfinder, at http://pathfinder.unm.edu/.

Accommodations: UNM is committed to providing equitable access to learning opportunities for students with documented disabilities. As your instructor, it is my objective to facilitate an inclusive classroom setting, in which students have full access and opportunity to participate. To engage in a confidential conversation about the process for requesting reasonable accommodations for this class and/or program, please contact Accessibility Resource Center at arcsrvs@unm.edu or 505-277-3506.

Credit Hour Statement: This is a three credit-hour course. Class meets for two 75-minute sessions of direct instruction for fifteen weeks during the Spring 2026 semester. According to federal guidelines, students are expected to complete a minimum of six hours of out-of-class work (including homework, study, assignment completion, and class preparation) each week. Honors courses generally demand more than six hours per week outside of class. You should budget at least ten hours a week for your reading and writing in this course.

Electronic Backups: You are required to keep electronic backups of all work you produce for this class that you can immediately provide upon my request.

Land Acknowledgment: Founded in 1889, the University of New Mexico sits on the traditional homelands of the Pueblo of Sandia. The original peoples of New Mexico Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache since time immemorial, have deep connections to the land and have made significant contributions to the broader community statewide. We honor the land itself and those who remain stewards of this land throughout the generations and also acknowledge our committed relationship to Indigenous peoples. We gratefully recognize our history.

Citizenship and/or Immigration Status: All students are welcome in this class regardless of citizenship, residency, or immigration status. I will respect your privacy if you choose to disclose your status. I support your right to an education free from fear of deportation. I pledge that I will not disclose the immigration status of any student who shares this information with me unless required by a judicial warrant, and I will work with students who require immigration-related accommodations. As for all students in the class, family emergency-related absences are normally excused with reasonable notice to the professor, as noted in the attendance guidelines above. UNM as an institution has made a core commitment to the success of all our students, including members of our undocumented community. The Administration’s welcome is found on the website: http://undocumented.unm.edu/.

Connecting to Campus and Finding Support: Students who ask for help are successful students. UNM has many resources and centers to help you thrive, including opportunities to get involved, mental health resources, academic support including tutoring, resource centers for people like you, free food at Lobo Food Pantry, and jobs on campus. Your advisor, staff at the resource centers and Dean of Students, and I can help you find the right opportunities for you.

Respectful Conduct Expectations: I am committed to building with you a positive classroom environment in which everyone can learn. I reserve the right to intervene and enforce standards of respectful behavior when classroom conduct is inconsistent with University expectations. Interventions and enforcement may include but are not limited to required meetings to discuss classroom expectations, written notification of expectations, and/or removal from a class meeting. Removal from a class meeting will result in an unexcused absence. Five or more unexcused absences may result in permanent removal and a drop from the course (see attendance policy). The University of New Mexico ensures freedom of academic inquiry, free expression and open debate, and a respectful campus through adherence to the following policies: D75: Classroom Conduct, Student Code of Conduct, University Policy 2240 – Respectful Campus, University Policy 2210 – Campus Violence.

UAP 2720 and 2740 Statement: Our classroom and university should foster mutual respect, kindness, and support. If you have concerns about discrimination, harassment, or violence, please seek support and report incidents. Find confidential services at LoboRESPECT Advocacy Center, the Women’s Resource Center, and the LGBTQ Resource Center. UNM prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex (including gender, sex stereotyping, gender expression, and gender identity). All instructors are “responsible employees” who must communicate reports of sexual harassment, sexual misconduct and sexual violence to Compliance, Ethics and Equal Opportunity. For more information, please see UAP 2720 and UAP 2740.

UNM Email Confidentiality Notice: Students often use email to inquire about protected and sensitive matters, including grades and class progress, and faculty often use email to individually report such protected and sensitive matters. Unless students opt out, in writing, to the Honors College, the Honors College and Honors Faculty will assume that all email sent individually to students via their official UNM email addresses (generally their @unm.edu address) is private and confidential and that the student assumes all risk of inappropriate interception of email transmissions. If students opt out of this policy, they are agreeing to receive such information only in person (and they may be required to show identification before information is shared with them) or through regular mail to the student’s official address on file with UNM.

Covid-19 Health and Awareness: I will be wearing an N95 mask in class and encourage you to do the same. UNM is a mask-friendly, but not mask-required, community. Masking is a simple and effective way to reduce the spread of respiratory illness and protect our shared learning environment. If you are experiencing respiratory symptoms or believe you may be contagious, I ask that you not attend class in person. Please email me so we can discuss reasonable alternatives for that day. I trust you to use this policy responsibly and to maintain regular attendance when you are well, so that if illness does occur, you can take the time you need to recover without falling behind.

READING LIST

I have prepared a coursepack of readings, available for a nominal fee ($52.00 as of Spring 2026) at the UNM Copy Center in Dane Smith Hall.

You will also need to purchase the following books in the specific editions on file at the UNM Bookstore:

Emerson, Self-Reliance and Other Essays (Dover Thrift Editions)- Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince (Cambridge, 1997)

- Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter (Dover Thrift Editions)

- Hobbes, Leviathan (Penguin Classics)

- Locke, Second Treatise of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration (Dover Thrift Editions)

- Machiavelli, The Prince (Chicago, 2nd ed., 1998)

- Marx & Engels, The Communist Manifesto (International Publishers)

- The MLA Handbook (9th ed., 2021)

- Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Bantam Classics)

Thoreau, Civil Disobedience and Other Essays (Dover Thrift Editions)- Walzer, On Toleration (Yale)

- Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (Dover Thrift Editions)

- Plus a good dictionary so that you can look up words without getting sucked into your phone

Other course materials may be distributed throughout the semester, either by email or on this class website. Students are responsible for obtaining these texts and bringing them to class: again, you should come to class prepared to discuss the readings in their entirety on the day they appear on the syllabus, even if we have fallen behind schedule.

This syllabus is subject to change, as I may announce changes in readings and adjust deadlines, ahead of time, in class, by email, or on this course website. It is very likely that we will drop some readings so that we can focus on the things that most interest us as a class. Check this website frequently for the most up-to-date schedule.

GOOD LUCK AND HAVE FUN!!